From killing to skilling: Ex-Maoists choose new course in Bastar school

A first-of-its-kind initiative launched by Chhattisgarh govt in the state’s Maoist hotbed is offering vocational courses for surrendered rebels. TOI visits the training centre to see how the path away from insurgency is being paved

As the reign of terror wanes in the Maoist heartland of Bastar in Chhattisgarh, authorities are on to another critical mission. The counteroffensive is not based on the usual strategies, but they hope it contributes towards the making of Bastar 2.0. Because this one aims to reshape the future of rebels who have laid down their weapons for a life of normalcy.

Not many residents of Bastar division’s Bijapur would know that tucked away behind high walls in one corner of the town is the state’s first formal rehabilitation centre for surrendered Maoists. When TOI visited the place, it found the first batch of 58 former Maoists — mostly aged 19-25 years — learning the basics of construction. Hands that once clicked bullets into magazines now picking up tricks of brickwork, eyes following the thread of a plumb line that once squinted down the sights of an AK-47.

School is cool

They start their day early, at 5.30 am, in much the same way as they would in the forests, with physical exercise. But what follows breakfast is a session in the classroom. During breaks, they play volleyball and badminton. Back in their quarters, they take turns to cook meals.

Most of them are illiterate. So, basic reading and writing is a must. Others get computer lessons. This batch is learning the ropes of building and construction. There are theory and practical classes. A slideshow presentation covered construction techniques, a coach and a translator explaining things in the Gondi dialect.

“Once, they stood around an instructor in the jungle, taking weapons and IED lessons. Now, they are watching a ‘mistri’ teach them how to ensure walls are straight and bricks are aligned,” said an officer.

Those among them who’d gone to school were forced to drop out in class 5 or 8 when Maoist recruiters came calling. “Guns slung across their shoul ders, the cadres would come with the diktat: ‘Give us at least 10 young girls and boys or the village will be ostracised’. Families that do not hand over a child do get ostracised. No ‘jal-jungle-jameen’ for them,” said a 20-year-old, who asked not to be named.

He surrendered recently after eight years as an outlaw. He remembers waking up in a panic at every slightest sound in the jungle. “Two more boys from my village had joined the Maoists along with me. Both were shot dead in encounters. I was heartbroken and terrified and decided to give up violence,” he said.

Another youngster, aged 19, recalled how miserable it was to sleep on wet ground in forest hideouts without a roof overhead. “In just two years, I felt I was done. It was horrible. Often, gunfire would jolt us awake in the middle of the night. I wanted desperately to get out, but it wasn’t easy,” he said.

Dial M for metamorphosis

The younger Maoists TOI spoke with were fascinated by gadgets. “On the rare occasions when we visited our village, we would see youngsters playing games or watching videos on their phones. And there we were, living miserable lives for an ideology that none of us understood or really believed in. Life in the jungle is very hard. After some time, you begin yearning for very basic things, like peaceful sleep,” said a 20-year-old.

As they embrace the mainstream, a police officer said that the “desire for a better life and easy access to mobile phones are diluting the younger cadres’ dedication towards Maoist ideology”. Their trainer, Ved Vyas Sahu, said he’s surprised how quickly the tribal youths are acquiring new skills. “There was an air of uncertainty on both sides in the beginning. We were not sure how far we would be able to go together. But it seems the former cadres have already undergone a lot of training in the outfit. The quality of their work shows their competence,” he said.

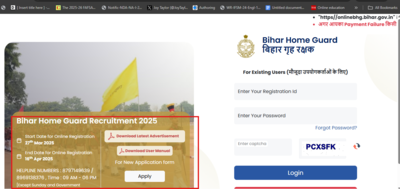

Bastar range inspector general of police P Sundarraj said that the surrendered cadres who are interested in other work, like textile and garments, are shifted to govt-run factories. “Many wish to study and are provided good education,” he said. Now, Chhattisgarh govt has decided to open similar rehab centres in each district headquarters in Bastar division.

BJP govt in Chhattisgarh has recently approved the State Naxal Surrender/Relief and Rehabilitation Policy-2025. One of its standout provisions allows panchayats in hypersensitive areas to declare themselves ‘Maoist-free’ and get work approvals worth Rs 1 crore.

Also, an official said, “If 80% or more cadres of a platoon/battalion/ area committee surrender together, then the state govt will pay them double the amount of bounty placed on their heads”. Besides, govt has decided to give 15,000 houses under PM Gramin Awas Yojana for surrendered Naxals and families affected by Maoist violence.

Reclaiming their lives

But turning a new leaf is not easy. Especially, for hardcore ultras. TOI spoke with one of the most dreaded Maoists of Bijapur, who is said to be behind the killing of more than 100 people. He admits that it was quite late before he realised that Maoist ideology was like “slow poison”. Locals weren’t happy when the benefits of Chhattisgarh’s rehabilitation policy for surrendered cadres were extended to him. He says it was how the insurgency works.

“When one leads a group of 100 Maoists as an area committee member or divisional committee member, all the killings carried out by the cadres under them are attributed to the leader. They are also the ones who get punished if a wrong person is killed.”

A govt officer said it’s about looking at the “bigger picture”. “It’s a big fight against a violent ideology… If we don’t wipe off their crime records after they surrender, other big commanders are less likely to give up arms.”

“The junior-ranked former cadres are given skill development training and are free to work as they want. The security of senior rank cadres is a matter of concern and they are usually settled around camps in the town itself and are trained to work as sentries or inducted in the District Reserve Guards,” the IG said.

An officer added that “they can’t be kept in barracks for long as they get frustrated and want to go out on operations”. “Surrendered Maoists can begin to go back to their native place if their region has enough security camps, but not to areas with a security vacuum.”

‘Weird and wonderful’

For the younger members at the camp, thoughts of making a fresh start bring an equal share of joy and jitters. “I was jumpy at first. We are used to watching over our shoulders all the time. Freedom felt weird and wonderful at the same time. Now, I will go back to my village and work as a mason at construction sites,” one of them said.

But will villagers accept them in their midst? “I feel that instead of disowning us, they will welcome our decision to surrender. They would be relieved that both their lives and ours are safe. We are all sons of the same soil,” said a 23-year-old.

TOI visited the village of one of these youths, around 30km from the district headquarters, where a villager said, “Takleef to hai, lekin sukoon bhi hai ki hinsa kam hogi (There’s the pain of the past, but relief, too, that the violence will decrease).”